Roller Coaster Energy: Worksheet Answers and Insights

The physics behind roller coasters is both thrilling and instructive, providing real-world examples of energy concepts that we often study in classrooms. In this article, we dive into the principles of roller coaster energy, with detailed explanations and insights into common worksheet questions. Here, we will provide answers and deeper understanding to help you or your students grasp how these amusement park wonders work.

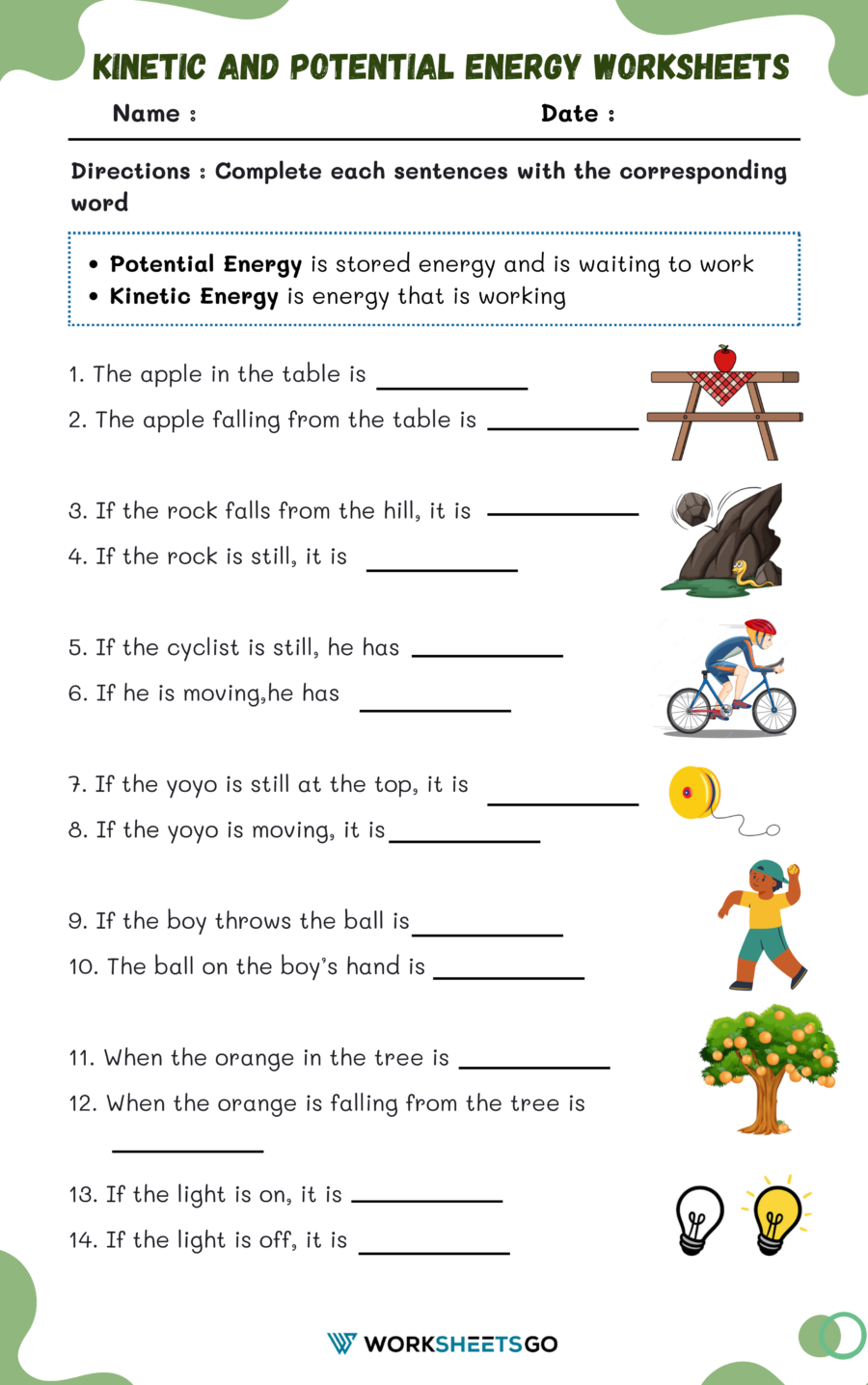

Understanding Potential and Kinetic Energy

At the core of roller coaster physics lie two key types of energy: potential energy and kinetic energy.

- Potential Energy (PE): This is the energy an object possesses due to its position relative to other objects. In a roller coaster, this energy is at its maximum when the car is at its highest point on the track. PE is calculated as PE = m * g * h, where m is mass, g is the gravitational acceleration, and h is the height.

- Kinetic Energy (KE): This is the energy of motion. As the roller coaster car starts to descend, potential energy converts to kinetic energy. KE is given by KE = 0.5 * m * v2, with v representing velocity.

🚂 Note: Remember, the total energy (sum of potential and kinetic) remains constant in an ideal, frictionless system.

Calculating Energy Transformations

Let’s consider a typical worksheet question:

Worksheet Problem:

A 500 kg roller coaster car is at rest at the top of a 100-meter hill. Calculate the potential energy, the kinetic energy when it reaches the ground, and the speed of the car at that moment.

| Energy Type | Formula | Calculation |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Potential Energy | PE = m * g * h | PE = 500 kg * 9.8 m/s² * 100 m = 490,000 J |

| Final Kinetic Energy | KE = 0.5 * m * v2 | Assuming no energy loss, KE at ground = PE initially = 490,000 J |

| Speed at the ground | v = √(2 * KE / m) | v = √(2 * 490,000 J / 500 kg) ≈ 44.27 m/s |

🌟 Note: The speed calculated assumes no air resistance or friction; real roller coasters might have energy losses due to these factors.

Conservation of Energy

At each point in a roller coaster’s journey, the sum of potential and kinetic energy equals the total mechanical energy initially available:

Etotal = PE + KE

- At the top of the hill, PE is high, KE is low.

- At the bottom, all PE has transformed into KE.

- Conservation of energy dictates that this sum remains constant throughout the ride, barring energy loss through friction or air resistance.

Practical Applications of Roller Coaster Physics

Beyond worksheets, understanding roller coaster energy has practical applications:

- Designing Roller Coasters: Engineers use these principles to design track layouts that maximize thrill while ensuring safety.

- Teaching: The dynamic nature of roller coasters helps teachers illustrate energy conservation in a vivid, real-world setting.

- Safety Considerations: By understanding where energy is transferred, designers can assess points of potential safety risks.

In summary, the study of roller coaster energy not only enhances our understanding of physics but also connects classroom theory to real-life excitement. From understanding how potential energy converts to kinetic energy as the car descends, to ensuring the safety of riders, these amusement park attractions are a perfect blend of fun and science.

Why does a roller coaster need a hill to start?

+

A hill at the start allows the roller coaster to gain potential energy, which is then converted to kinetic energy to propel the coaster through the track.

What happens to the energy when a roller coaster comes to a stop?

+

The kinetic energy is transformed into heat, sound, and work against friction. In a real system, some energy is lost due to these factors.

Can roller coasters gain more energy during the ride?

+

Energy typically does not increase after the initial lift. However, elements like loops or hills can temporarily increase kinetic energy at the expense of potential energy.

How does friction affect a roller coaster’s energy?

+

Friction reduces the mechanical energy of the coaster, transforming it into heat, which explains why real-world roller coasters need a slight upwards slope to maintain momentum or additional energy boosts.