Momentum Impulse Worksheet: Mastering Physics with Ease

Understanding Momentum and Impulse in Physics

Physics, often considered one of the more challenging subjects, can actually be very straightforward once we understand its core principles. Among these principles, momentum and impulse are pivotal. These concepts not only simplify the understanding of how objects move and interact but are also crucial for solving complex problems in mechanics.

The Fundamentals of Momentum

Momentum is a property that quantifies the motion of an object, considering both its mass and velocity. Here's how we define and calculate momentum:

- Definition: Momentum, denoted by p , is the product of an object's mass m and its velocity v .

- Formula: p = m \cdot v

The unit for momentum is \text{kg} \cdot \text{m/s} . Momentum is a vector quantity, which means it has both magnitude and direction. Here are some key points about momentum:

- Conservation of Momentum: In an isolated system where external forces are negligible, the total momentum before an event equals the total momentum after.

- Inelastic Collisions: When objects stick together, or there is a deformation, momentum is conserved, but kinetic energy might not be.

- Elastic Collisions: Both momentum and kinetic energy are conserved.

💡 Note: Always verify the conservation of momentum in both inelastic and elastic collisions by calculating total momentum before and after the interaction.

Exploring Impulse

Impulse provides another lens through which we can look at the change in an object's motion. Here's what you need to know about impulse:

- Definition: Impulse, denoted by J , is the change in momentum of an object when a force is applied over time.

- Formula: J = F \cdot \Delta t where F is the force, and \Delta t is the time over which the force acts.

Impulse can also be understood as the area under the force-time graph, giving a visual representation of the applied force's effect on an object:

| Force | Time | Impulse |

|---|---|---|

| Constant Force | \Delta t | J = F \cdot \Delta t |

| Varying Force | \Delta t | J = \int_{t_1}^{t_2} F(t) \, dt |

Here are key takeaways regarding impulse:

- Force-Time Graph: Impulse is the area under the curve in the force-time graph.

- Impulse-Momentum Theorem: Impulse equals the change in momentum ( J = \Delta p ).

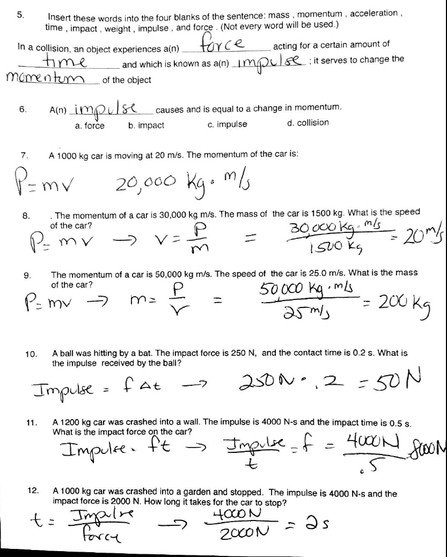

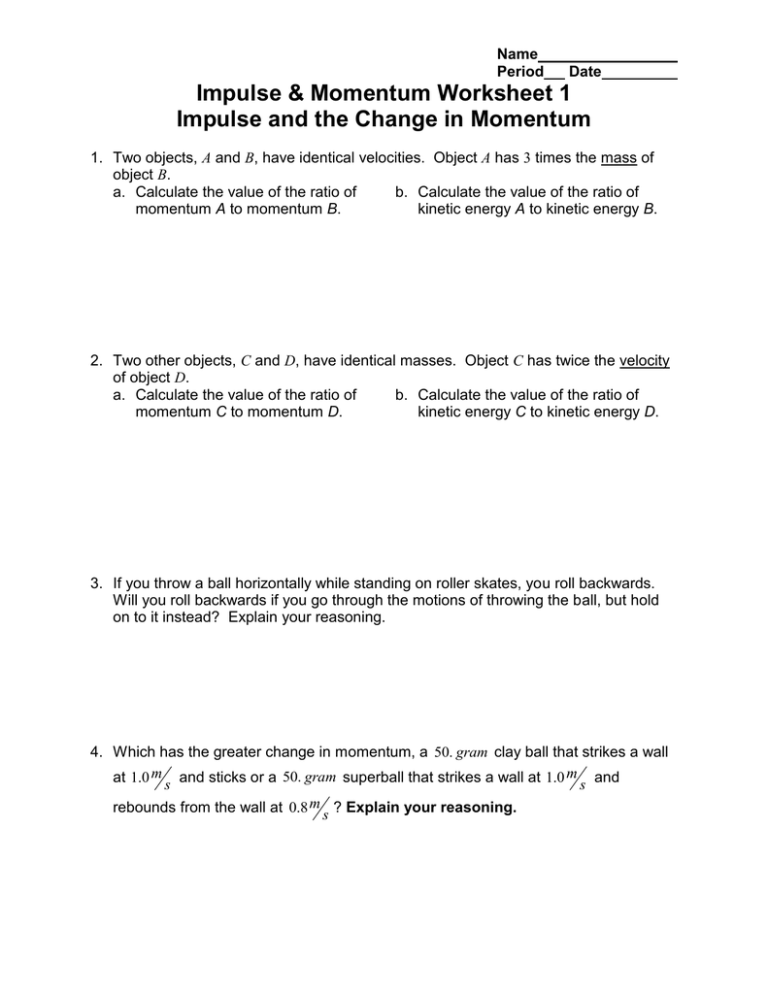

Worksheet: Practical Application of Momentum and Impulse

Let's dive into some practical examples and problems to cement your understanding of these concepts:

Example 1: Car Collision

A 1500 kg car traveling at 25 m/s rear-ends another car at a stoplight. After the collision, both cars move forward with a combined velocity of 10 m/s. Calculate:

- The initial momentum of the moving car.

- The final momentum of both cars together.

- The change in momentum for the moving car.

Solution:

Using ( p = m \cdot v ):

- Initial momentum of the moving car: ( p = 1500 \, \text{kg} \cdot 25 \, \text{m/s} = 37500 \, \text{kg} \cdot \text{m/s} )

- Final momentum of both cars: ( p = (1500 \, \text{kg} + \text{mass of second car}) \cdot 10 \, \text{m/s} )

- Change in momentum for the moving car: ( \Delta p = 37500 \, \text{kg} \cdot \text{m/s} - (1500 \, \text{kg} \cdot 10 \, \text{m/s} + \text{final momentum of second car}) )

💡 Note: Ensure the direction of momentum is considered correctly. The moving car's initial momentum is positive, while the stationary car has zero initial momentum.

Example 2: Impulse in Sports

A tennis player hits a tennis ball with a racket. The ball, with a mass of 58.5 grams, is initially traveling at 30 m/s. The racket applies an average force of 200 N for 0.1 seconds. Calculate the:

- Impulse on the tennis ball.

- Change in velocity of the tennis ball.

Solution:

Using ( J = F \cdot \Delta t ):

- Impulse: ( J = 200 \, \text{N} \cdot 0.1 \, \text{s} = 20 \, \text{N} \cdot \text{s} )

- Change in momentum: ( \Delta p = J = 20 \, \text{N} \cdot \text{s} )

- Change in velocity: ( \Delta v = \frac{\Delta p}{m} = \frac{20 \, \text{N} \cdot \text{s}}{0.0585 \, \text{kg}} \approx 341.88 \, \text{m/s} ) (assuming mass in kg)

Example 3: Rocket Propulsion

A rocket with a mass of 3000 kg has an exhaust velocity of 3000 m/s and expels mass at a rate of 5 kg/s. Calculate the:

- Impulse provided by the rocket's engine every second.

- Change in velocity of the rocket per second assuming no external forces.

Solution:

- Impulse per second: ( J = \frac{dm}{dt} \cdot v_{\text{exhaust}} = 5 \, \text{kg/s} \cdot 3000 \, \text{m/s} = 15000 \, \text{N} \cdot \text{s/s} )

- Acceleration: ( a = \frac{F}{m} = \frac{15000 \, \text{N}}{3000 \, \text{kg}} = 5 \, \text{m/s}^2 )

- Change in velocity per second: ( \Delta v = 5 \, \text{m/s}^2 \cdot 1 \, \text{s} = 5 \, \text{m/s} )

These examples highlight how momentum and impulse are intertwined in real-world scenarios, making physics not just theoretical but applicative and engaging.

What is the difference between elastic and inelastic collisions?

+

In an elastic collision, both kinetic energy and momentum are conserved. This means that the total kinetic energy before and after the collision remains the same. Conversely, in an inelastic collision, while momentum is conserved, kinetic energy is not; some energy is usually converted into heat, sound, or deformation energy, meaning the objects might stick together or get deformed.

Why is the conservation of momentum important?

+

The principle of momentum conservation is crucial because it's a natural law stemming from Newton's third law (action-reaction). It simplifies problem-solving in physics by allowing us to predict the motion of systems when external forces are minimal or negligible. This principle underpins various applications, from understanding car crashes to calculating the motion of celestial bodies.

How does the time over which a force is applied affect impulse?

+

Impulse J is directly proportional to both the force F and the time \Delta t over which the force is applied. A larger force or a longer time results in a greater impulse, which in turn causes a larger change in momentum. This is why airbags in cars (which increase the time of impact) can reduce the force experienced by passengers during a collision, thereby decreasing the likelihood of injuries.

Can you provide an example of impulse in daily life?

+

A real-life example of impulse is when you catch a fast-moving ball. The ball’s momentum is high, so your hand naturally extends the time of contact, thereby reducing the force on your hand and making the catch less painful. This is an application of the impulse-momentum theorem where J = F \cdot \Delta t , allowing the force F to be lower by increasing \Delta t .

How does momentum relate to the principles of motion?

+

Momentum is intricately linked to the principles of motion through Newton's laws. According to Newton's first law, an object at rest tends to stay at rest, and an object in motion stays in motion unless acted on by an external force. Momentum adds to this by quantifying how much motion an object has, including its mass and velocity. In the absence of external forces, momentum remains conserved, allowing for the prediction and understanding of motion in systems.

To summarize, understanding momentum and impulse in physics involves grasping how objects move and interact with each other. Momentum, defined as mass times velocity, is a fundamental concept that helps us analyze physical interactions, particularly in collisions. Impulse, on the other hand, measures how much force acting over time changes an object’s momentum. Both concepts are essential for problem-solving in mechanics, providing a framework for predicting the outcomes of various physical scenarios, from daily life phenomena to complex scientific experiments. Remember that momentum conservation simplifies analysis, while impulse allows us to account for force-time relationships, giving us a powerful toolset to master physics with ease.